After the hajj: Mecca residents grow hostile to changes in the holy city

As millions of hajj pilgrims return home, Meccas two million locals are left struggling with the impacts of their changing city. Much of old Mecca has been razed and rebuilt to make room for growing tourism, forcing out residents

Millions of hajj pilgrims are preparing to head home, after five days performing ancient rites, revering a God omnipresent in the city of Mecca.

They have stoned figurative devils, they have slept in the worlds largest tent city, they have drunk water from the Zamzam well together: a heaving throng of nearly two million people from all over the world.

Circling the Kaaba, the black cubic epicentre of this sanctuary city, pilgrims would have looked up to see one of the minarets of the Grand Mosque, dwarfed by Abraj al-Bait clocktower, a much-maligned luxury hotel and commercial complex and the second-tallest building in the world.

Next year, they will see the Abraj Kudai, the largest hotel on Earth.

Indeed, though rebuilt throughout the centuries, the minarets like much of the city are now relics of a pre-modern Mecca. Cranes and scaffolding now dominate the central skyline, reminders that the city is undergoing a massive state-run expansion to be able to handle ever-increasing numbers of annual pilgrims in the future.

But as much as these pilgrims as much as any Muslim belong to Mecca for those five days, they are but spiritually home. When it comes to the city they visit out of religious obligation and devotion to God, most are transient figures, who will leave no indelible mark on the city. They leave behind two million locals, who are struggling with the impacts of the changing nature of their city.

In the 1960s, before travel became more affordable, hajj pilgrims numbered roughly 200,000. According to Meccas mayor, today there are two to three million of them, with an additional 12 million performing the lesser pilgrimage of umrah, which can be done at any point throughout the year. Faced with a dip in oil prices, revenue from Meccan tourism is expected to become a greater source of revenue for the Saudi Kingdoms economy. Under its current plans, the city expects to add several million more pilgrims a year by 2020.

Estimates vary, but only a handful of Meccas millennium-old buildings remain. Ottoman fortresses and hills have made room for the royal clocktower. The prophets first wife Khadijahs home is now the site of public lavatories. But very little is said about the thousands of homes and neighbourhoods destroyed to make way for the citys expansion. Thirteen of Meccas 15 old neighbourhoods have been razed and rebuilt to make room for hotels and commercial spaces.

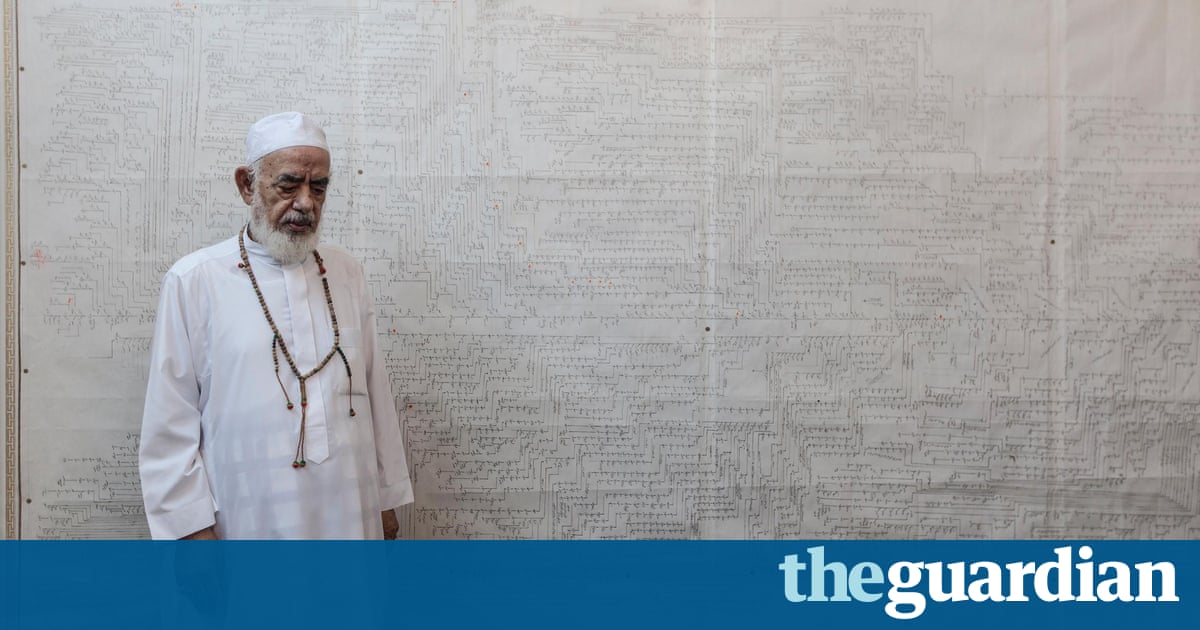

No one knows this better than Sami Angawi.

An architect who now lives in Jeddah, Angawi spent his childhood in his familys ancestral home of Mecca. Like many Meccans, then as now, his father was a local guide to pilgrims there for umrah or hajj. As a boy, Angawi has said he would help his father carry around pilgrims shoes while they prayed.

The Angawis lived in Shab Ali, the neighbourhood said to have been the place of the prophet Muhammads birth. But their home was demolished as part of the first organised expansion of the Grand Mosque in the 1950s. Angawi told Al Jazeera last year that his family was forced to move two more times as the city continued its forced expansion.

The 65-year-old architect is also the founder of the Hajj Research Centre, who has spent the last three decades researching and documenting Mecca and Medinas historic sites. They are turning the holy sanctuary into a machine, a city which has no identity, no heritage, no culture and no natural environment, Angawi told the Guardian in 2012.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/sep/14/mecca-hajj-pilgrims-tourism