‘Anarchy on Sunset Strip’: 50 years on from the ‘hippie riots’

In November 1966, the birthplace of the hippie movement was shaken by a confrontation that was an early salvo in the culture wars to come

Fifty years ago this week, a riot took place on Los Angeless famous Sunset Boulevard. Bemused reports appeared in the days that followed with headlines like Long Hair Nightmare: Juvenile Violence on Sunset Strip, and Anarchy on Sunset Strip. All of them speculating on why middle-class, mainly white, youths should riot on a street better known for elegant Hollywood nightspots. Although the street cuts through Los Angeles, from Figueroa Street to the Pacific Coast highway, the riot, AKA the hippie riots and the Sunset Strip Curfew Riots, occurred right in its heartland, in and around 8118 Sunset Blvd, just off Crescent Heights. The focal point was Pandoras Box, originally a jazz club but since 1962 an independent music venue and gathering place for long-haired and mini-skirted youths in search of music, recreational drugs and casual sex.

From the perspective of local bankers, restaurateurs and real estate moguls, the alcohol-free, purple and gold Pandoras Box, located on a mid-boulevard traffic island, had become a magnet for an unseemly, ie cash-strapped, possibly subversive, crowd. Business leaders railed against the newcomers, claiming they were causing late-night traffic congestion. Their answer: remove the island, widen the road, put in a three-way traffic signal and turn the locale into a high-rise business area. To facilitate their plan, local businesses pressed the city council to pass ordinances that would ban loitering, establish a 10pm curfew, and demolish the building once and for all.

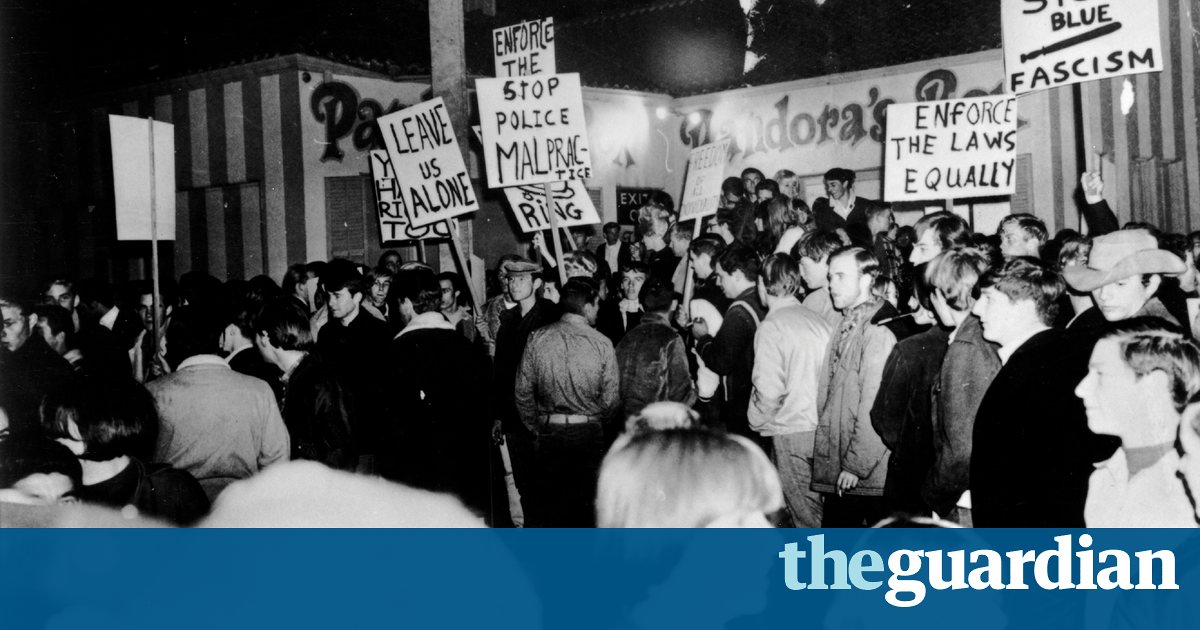

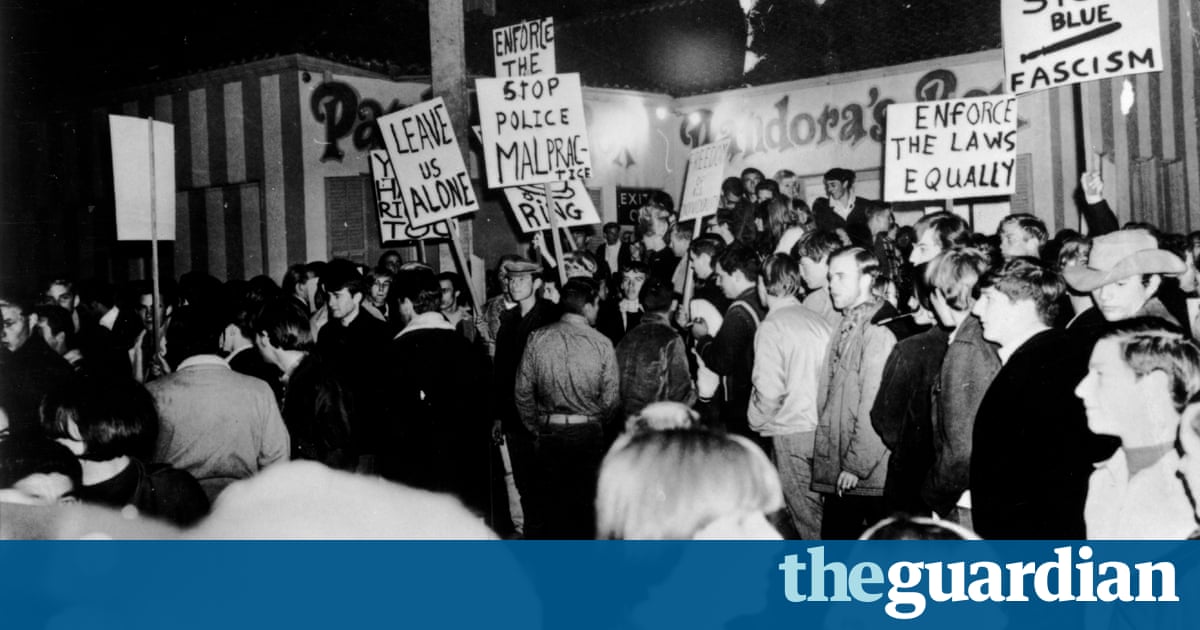

For those who congregated in the area, their soundtrack consisting of Dylan, the Byrds, Frank Zappa, Buffalo Springfield, Love and the Doors, the curfew was nothing less than an infringement of their civil liberties and right to gather in public. This exacerbated by the fact that over the previous months police had arrested thousands of young hippie-types, most of them guilty of nothing more than hanging out on particular streets. Which is why on 12 November, the Fifth Estate coffee house, located a block from Pandoras Box, printed and passed out flyers that read, Protest Police Mistreatment of Youth on Sunset Blvd. No More Shackling of 14 and 15 year olds. Written by two teenagers, the flyers called for a peaceful protest that night in front of Pandoras Box. Local radio disc jockeys announced the event as well. That night about 3,000 teenagers showed up carrying signs with slogans like Cops Uncouth to Youth and Give Back Our Streets. Also in attendance was a smattering of hip Hollywood, such as Jack Nicholson, Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda.

Faced with a multitude of protesters, the police realized enforcing the curfew might only make matters worse, and so tried to stay calm and out of the way. But when a scuffle broke out, the result of a minor road accident, 155 LAPD officers and 79 sheriffs deputies moved in with teargas and batons, turning what had been a relatively peaceful gathering into a something far uglier. Ordered to disperse, the crowd responded by hurling rocks and bottles at the police, smashing windows and overturning vehicles.

The areas pro-business county supervisor, Ernest Debs, called the youths misguided hoodlums. While Captain Charlie Crumly, commander of the LAPDs Hollywood division, insisted that leftwing groups and outside agitators had organized the protest, going on to say that there are over a thousand hoodlums living like bums in Hollywood, advocating such things as free love, legalized marijuana and abortion. No doubt such statements contributed to the sporadic disturbances that continued on the Strip over the next few months.

Dissatisfied with coverage in the local press and use of the term riot to describe events on the Strip, the Byrds manager and Elektra record producer, Jim Dickson, teamed up with the Beatles and Beach Boys press officer, Derek Taylor. With support from the Woolworth heir Lance Reventlow and Gilligans Island actor Jim Denver, they formed Community Action for Facts and Freedom (CAFF), which, among other things, organized a benefit concert to raise bail money for those arrested and help pay for damaged property. Although the Strip was somehow able to maintain its status as an unofficial counterculture zone, a number of licenses were withdrawn and clubs closed. Later in the month the city council acquired Pandoras Box. It was the same month in which Ronald Reagan was elected governor, an propitious start to his rise to power. The following year saw the demolition of Pandoras Box. These days what was Pandoras Box is nothing more than a triangular concrete slab, while the sleazy appeal of the Strip has been replaced by corporate logos and pay-to-play venues.

Looking back, one might say that the November riot was influenced by the infinitely more important Watts insurrection of a year earlier. However, it was probably closer in spirit to the wave of generational and predominantly white challenges to authority which, during the 1950s and 1960s, centered on the right to inhabit the street at night. These came from various quarters, like the cruising subculture, which, in that era of cheap gas and wide roads, took the form of driving down main thoroughfares, as in American Graffiti, and drag racing, as in Rebel Without a Cause. Challenges also came from that eras surfing subculture, whose young legions were set on garnering what freedom they could within relatively restrictive boundaries. For either, occasional confrontation was inevitable. Though the riots on the Strip couldnt compare to the 11 riots that took place in a six-month period in 1961, disturbances that stretched from Zuma Beach, where 25,000 teenagers showed up to pelt the police with sand-filled beer cans, to faraway Alhambra, Rosemead and Bell, prompting articles in the press to the effect that such confrontations must surely have been communist-inspired.

With curfews commonplace in many towns and cities, these disturbances were, whatever the instigating complaint, about who controls public space and the right to congregate in those spaces. At the same time, such events did much to politicize many of their participants, graduating as some would from adolescent disrespect for arbitrary authority to larger issues, such as protesting against the war in Vietnam and supporting jailed Black Panthers.

How important was the Sunset Strip riot? With business interests on one side, and peace and love advocates on the other, it was, if nothing else, an early salvo in the culture wars, a battle which continues to this day, with conservatives continuing to blame societys ills on what they perceive as the permissiveness of that era.

Perhaps the riots most lasting effect had to do with the music that came out of that event. At least when it comes to Buffalo Springfields For What Its Worth, now heard ad nauseam in beer adverts, movies, TV shows, plays and just about any film footage depicting a confrontation between police and demonstrators. But there were other, lesser known, songs, like the Standells ridiculous Riot On Sunset Strip, the hilariously sincere S.O.S. by Terry Randall, the equally fervent Open Up the Box Pandora by the Jigsaw Seen, the plaintive Scene of the Crime by Sounds Unreal, the bathetic Safe In My Garden by the Mamas and the Papas, and, arguably the most interesting of the lot, Frank Zappas Plastic People. There was also the kitsch B-movie, Riot on Sunset Strip, directed by Arthur Dreifuss (whose career went from directing Brendan Behans The Quare Fellow to exploitation mishaps like The Love-In and The Young Runaways), which includes footage of the riot, and, incredibly enough, was released within four months of the original disturbance.

Eventually, business interests would find a way to profit from the peace and love market, exploiting its music and fashion, while co-opting its language for political gain. Within a couple of years a street that had been a fairly benign, even innocent, meeting place had mutated into a mecca for dropouts, acid casualties, bikers, consumers of bad speed, exploitative entrepreneurs and sexual predators. Be that as it may, the Sunset Strip riot is best thought of as a statement regarding the right to congregate, part of a protest movement that continues to this very dayand includes such diverse sites as Stonewall, Zuccotti Park, Tahrir Square and the streets of Ferguson, Missouri. Maybe what was happening on Sunset Boulevard, as the song says, wasnt exactly clear, but it was certainly part of a process to own the night, reclaim the streets and say no to arbitrary authority.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/11/sunset-strip-riot-hippie-los-angeles